Entry #4

October 1, 2025

“What’s with the attitude? Are you on your period? Stop PMS-ing!” With the number of times us uterus-bearing, period-having people have heard these comments I’m confident we could buy our own island, build a dinosaur-themed amusement park, and procure an endless supply of caviar. These statements have become so “mainstream,” that I doubt anyone using them ever thinks about the underlying context. Let’s start at the center of it all, hormones.

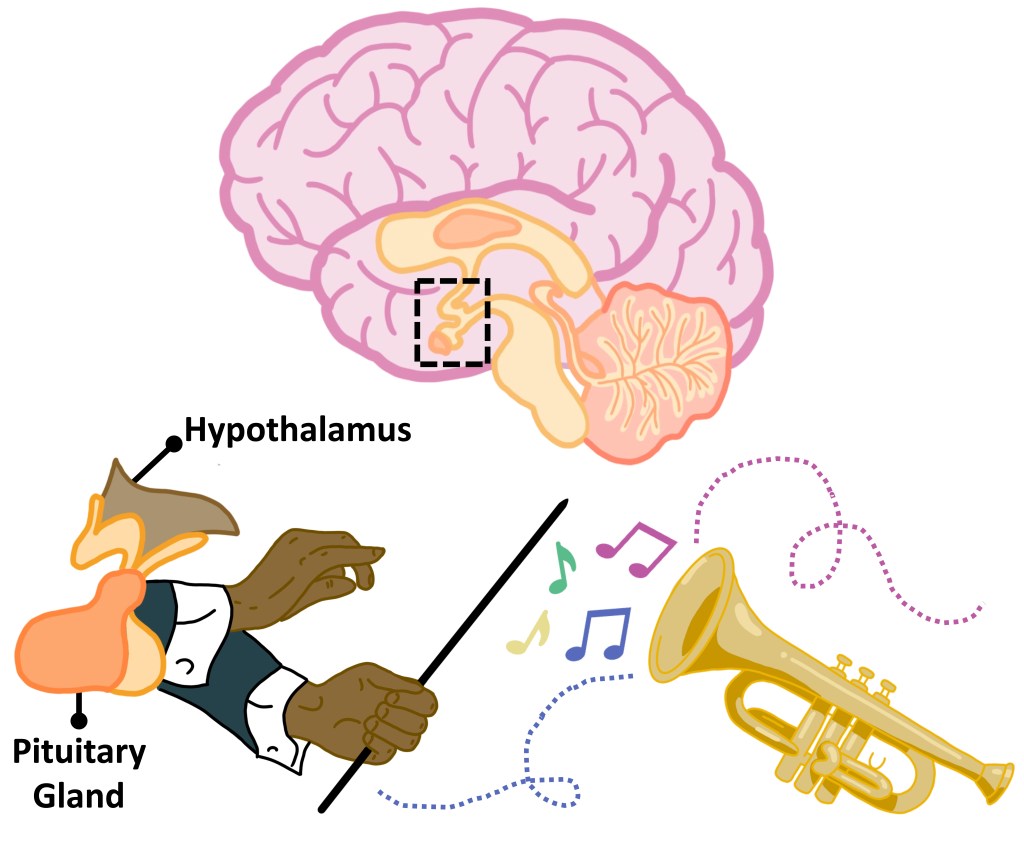

Hormones are a part of the endocrine system. You can imagine this system like an orchestra. The brain is home to the conductors (hypothalamus or pituitary gland) that dictate when and which musicians (other endocrine glands) throughout your body produce music notes (hormones). The music changes across the menstrual cycle, rising and falling in overlapping patterns.

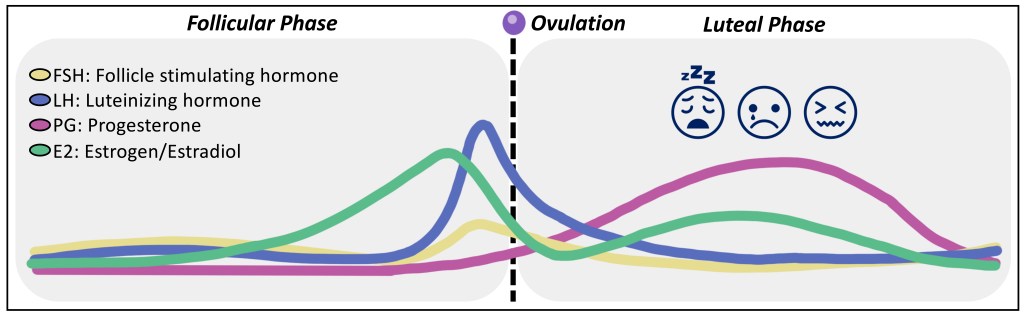

The Follicular Phase occurs when the ovaries are preparing to release an egg and the uterus is getting ready to receive it once fertilized. During this early stage, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), produced by the pituitary gland, begins to increase and triggers follicle growth within the ovary. At the same time, pituitary gland production of luteinizing hormone (LH) also increases – preparing the ovary to release an egg. Estrogen, specifically Estradiol (E2) is another key player in the follicular phase and thickens the uterine lining (endometrium). Upon ovulation, or release of an egg from the ovaries, progesterone (PG) increases to further prep the uterus for implantation and to prevent release of any additional eggs. If there is no fertilization event, FSH, LH, and E2 all decrease to make way for the dreaded Luteal Phase. I say dreaded because the sudden decline in these hormones leads to menstruation accompanied by several unpleasant symptoms including physical cramping, bloating, tiredness, and emotional upheaval typically referred to as “premenstrual syndrome”, or PMS.

We know that the menstrual cycle occurs for the biological purpose of bearing children, but there is still a lot to uncover. For example, recent studies have begun to focus on consequences of such rises and falls in menstrual hormones.

Now I don’t know about you, but my personal experience with PMS symptoms involves more than just crying over cute puppies or craving chocolate. Each week before my period hits me, I am inundated with feelings of absolute dread – wanting to just give up on all my life endeavors and become one sluggish blob with my mattress. (We’re talking quit your school/job and jump in front of traffic type of feelings.) But no matter how hard I try, I can’t prevent these thoughts even now knowing they follow my natural hormone cycle. One night when I couldn’t fall asleep from unstoppable, unexplained crying I came across a new term, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or PMDD. Being the science geek I am, I went straight to PubMed for more information.

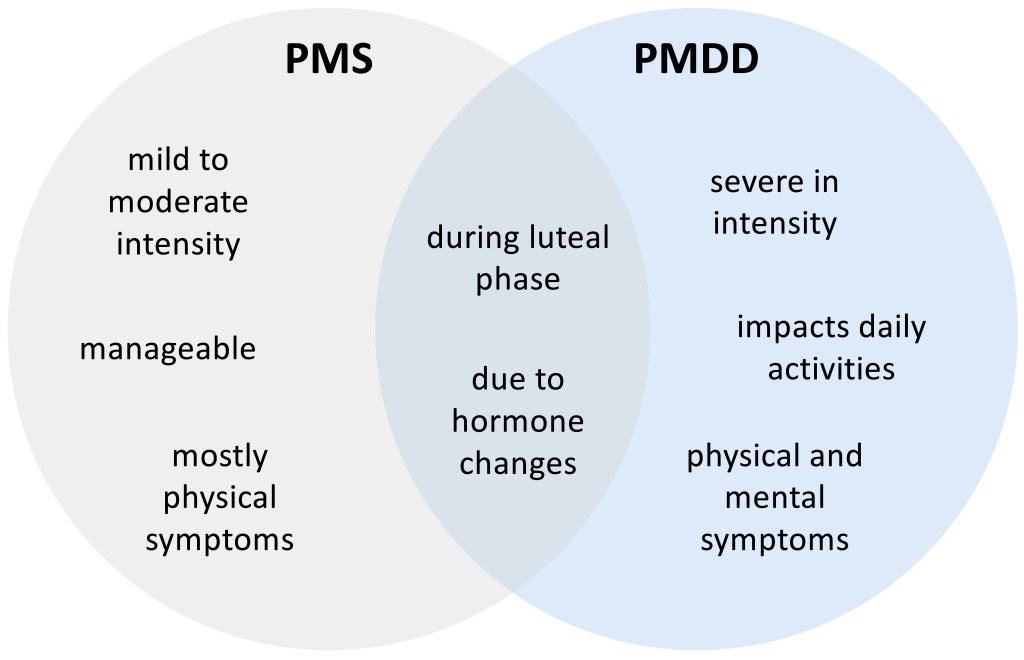

PMS vs PMDD

PMS and PMDD symptoms both occur during the “dreaded” luteal phase, about 1-2 weeks prior to menstruation. While some symptoms are shared between both (i.e. fatigue, bloating, headaches, cravings, mood swings), what really sets PMDD apart is the severity of symptoms. For example, while somebody experiencing typical PMS may have feelings of sadness, somebody with PMDD may experience debilitating depression and/or anxiety. Significantly, these extreme emotions follow the luteal phase with onset occurring alongside the hormone drop and resolution at the start of menstruation.

PMDD Risk Factors

Like many disorders and diseases, the risk of developing PMDD is not entirely random. Research finds that PMDD onset occurs in the mid-20s to 30s on average; I noticed a dramatic change in symptom severity around age 27. Panic (anxiety) disorder is also a contributing factor; I was diagnosed with general anxiety disorder prior to developing PMDD. Stress is considered a risk factor for most disorders including PMDD; I was a PhD student at the time of my diagnosis, enough said. Lastly, family history of PMDD or other mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety has also been linked to disorder development. I can’t speak on historical PMDD in my family, but mental health conditions are traceable.

PMDD Treatment

Treatments for PMDD are not “one size fits all.” Of course, to receive treatment you must first be formally diagnosed. Unfortunately, there is no quantitative readout to suggest PMDD. Providers must rely purely on anecdotal patient accounts and reported symptoms that intersect with the hormone cycle. Current approaches to treatment are centered in alleviating the most debilitating symptoms, for example depression and anxiety. In these cases, providers often turn to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs); I take Lexapro for my symptoms. Other treatments may include cognitive behavioral therapy, hormonal birth control, hormone replacement therapy, and lifestyle changes. Hopefully with more research focused on the biology behind PMDD, more specific treatments can be developed.

The Future of PMDD Research

Although the number of peer-reviewed articles on PMDD have been increasing since the 1980s, the validity of PMDD is still unfortunately debated. For example, the annual 1986 American Psychological Association (APA) meeting report contained an article titled “Research Evidence Does Not Support the PMDD Diagnosis” arguing against PMDD as a “real” disorder. In October of 2022, the same organization published a cover story titled “Is PMDD real?” Oof. There is nothing worse than knowing deep down that what you are experiencing is definitely real and then seeing a title like that. Interestingly, in July of 2023 APA issued an article discussing “PMS vs PMDD: What’s the difference?”. So, it seems that PMDD is slowly being accepted as more than a bunch of dreaded luteal phase symptoms. Even the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) now recognizes PMDD as a disability (when symptoms are life-limiting).

What about PMDD research efforts? Thankfully, there are groups working towards understanding both the underlying causes of PMDD and developing better tools for diagnosis. One clinical trial that just began in September of 2025 is hoping to address the latter issue. Using their previously identified postpartum indicators as a reference, Liisa Hantsoo, Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins RMHC) aims to determine if these biomarkers also indicate PMDD through collecting blood samples of participants while closely monitoring mood changes across the menstrual cycle. I just might have to get involved in this one!

Overall, I hope that you learned something new from reading this blog post. At the very least, please consider the importance of studies related to women’s health. More than ever women’s health studies are at risk, with the recent loss of major NIH’s Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) projects as just one example.

CC

Sources:

- Clay, R. A. (2023, July 31). PMS vs. PMDD: What’s the difference? https://www.apa.org/topics/women-girls/pms-vs-pmdd

- Cook BL, Noyes R Jr, Garvey MJ, Beach V, Sobotka J, Chaudhry D. Anxiety and the menstrual cycle in panic disorder. J Affect Disord. 1990 Jul;19(3):221-6. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90095-p. PMID: 2145343.

- Daw, J. (2002, October 1). Is PMDD real? Monitor on Psychology, 33(9). https://www.apa.org/monitor/oct02/pmdd

- Draper, C.F., Duisters, K., Weger, B. et al. Menstrual cycle rhythmicity: metabolic patterns in healthy women. Sci Rep 8, 14568 (2018). doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32647-0

- Hamilton JA, Gallant SJ. Debate on late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1990 Aug;147(8):1106-7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.8.aj14781106. PMID: 2375459.

- Hantsoo L, Payne JL. Towards understanding the biology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: From genes to GABA. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023 Jun;149:105168. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105168. Epub 2023 Apr 12. PMID: 37059403; PMCID: PMC10176022.

- Keijser, R., Hysaj, E., Opatowski, M., Yang, Y., Lu, D. (2024). Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Etiology, Risk Factors and Biomarkers. In: Martin, C.R., Preedy, V.R., Patel, V.B., Rajendram, R. (eds) Handbook of the Biology and Pathology of Mental Disorders. Springer, Cham. doi:

- Mirin AA. Gender Disparity in the Funding of Diseases by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021 Jul;30(7):956-963. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8682. Epub 2020 Nov 27. PMID: 33232627; PMCID: PMC8290307.

- Naik SS, Nidhi Y, Kumar K, Grover S. Diagnostic validity of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: revisited. Front Glob Womens Health. 2023 Nov 27;4:1181583. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2023.1181583. PMID: 38090047.

- Wadman M, Kaiser J, Reardon S. NIH guts its first and largest study centered on women. Science Insider. 2025 April 22; doi: 10.1126/science.zwfom6i

- Cleaveland Clinic

- Clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT06771583

- Mayo Clinic

Leave a comment